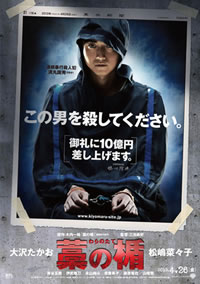

The Cinema of Japan Trailer for your Weekend: Shield of Straw

Of all the directors featured this week, Takashi Miike is one who is still working relatively prolifically. So I thought it might be good to feature his upcoming (or recently released depending on where you live) film as this week’s trailer.

Shield of Straw (or Straw Shield depending on who you ask) looks like some pretty violent and stylish Miike fare focusing on the cop genre. Unfortunately I could not find a trailer with English subtitles, but just from the visuals, this looks like one that I wouldn’t mind catching. What do you guys think?

This week thanks to Madman Entertainment, you have the chance to win a copy of Ace Attorney, Black Belt plus one other Japanese film on DVD. Head here for all the details on how to enter.

Like what you read? Then please like Not Now I’m Drinking a Beer and Watching a Movie on facebook here and follow me on twitter @beer_movie.

The Cinema of Japan: Reel Anime Reviewed

Reel Anime is an annual travelling anime festival that travels around Australia around this time each year. I have been lucky enough to see three of the films in this year’s fest, so I though that this week focusing on Japanese film was the ideal time to take a look at them.

A Letter to Momo (2011) is about as close to Studio Ghibli as a film can get, without actually being made by Ghibli. This is not meant to be a criticism, it is just the film pretty openly wears influences such as Spirited Away (2001) on its sleeve.

Like all three of these films, the animation in this one is incredibly beautiful. In A Letter to Momo it is the use of colour that most stands out, feeling like as much care has gone into the choice and use of colour as all the other aspects of the visual approach. The simple concept is a wonderful one that allows the filmmaker to gradually incorporate a more fantastical world into proceedings. Momo is a young girl who misses her recently deceased father. Her grief, and resultant emotional distance from those around her, is exacerbated by the fact that she had argued harshly with her father the last time that she saw him. One of her prized possessions is a letter he had begun to write to her following this which simply reads “Dear Momo”. Momo spends a lot of time holding this letter, looking at it hoping for a flash of insight as to what her father would have written next. Into this world come a number of spiritual beings or monsters that only Momo can see.

Some of this has been done before. Momo has been moved to a new town and her struggles to fit in are heavily reminiscent of The Karate Kid (1984) and a myriad of other films. Likewise the idea that there are monsters visible only to a child did not initially grab me. But as the film progresses, and the really fun personalities of Momo’s new spiritual companions (or light-hearted tormenters) come to the fore, there is a lot of fun here and also an original sensibility that at least in part stops the film from simply becoming ‘Ghibli-lite’. The interaction between Momo and these charismatic beings us quite charming I think and ranges from the extremely cheerful to flashes of if not malice, than at least the generation of some strong negative emotion. Also as the film progresses, the emotional relationships Momo has with her mum and grandad are explored more and more. I wish there was more of both these characters because the exploration of how Momo’s relationship with them is influenced by the grief of all three parties works extremely well.

This is definitely not anime in the mind blowing, searing sense. But as a gentle emotional journey with plenty of fantastical lashings, A Letter to Momo definitely succeeds a lot more often than not.

Verdict: Stubby of Reschs

With a title like 009: Re Cyborg (2012), I was hoping for some balls out, full on huge robot fighting action. However this is possibly because I don’t really know what a cyborg is.

As the film begins, suicide bombers obeying “His Voice” are destroying cities worldwide. This leads to the bringing together of an Avengers style cyborg superteam to try and deal with matters. The animation style is super artistic, bringing to life the urban sensibility through a washed out approach. There are a number of thumping action sequences that have a very cool, street based sensibility to them as well, which is helped no end by a really good soundtrack.

Whilst there is no doubting that some of what went on went over my head a little, 009: Re Cyborg is an extremely interesting film. At times the film is awash with biblical references and the plot goes into some complicated territory. The latter one is a bit of an issue though. As the narrative spirals to include a U.S. government conspiracy… or something like that anyway, my mind began to wander and the film lost its grip on my focus. This is not helped by a tendency to get bogged down in religious, philosophical and psychological babble through the second half of the film. But the film on balance gets away with it all because it is so interesting. Even if you lose exactly what is happening there are still cool things to appreciate, allusions to classical private eye films and a strong thematic concern with the military industry and the disruption of peace for profit.

When 009: Re Cyborg is doing action, it is doing it awesomely. The long stretches of talking that fill in the gaps are less engaging. But if action anime is your thing, then you will probably be happy enough to sit through that for the good bits.

Verdict: Stubby of Reschs

At just 44 minutes long, The Garden of Words (2013) is either a long short film or a short feature. Whatever it is, it is my favourite of these Reel Anime films I have seen. It also does not really sit comfortably within the realm of any anime I have seen before.

The film is essentially a love story between a 15 year old boy and a 27 year old woman. Not a love story in the passionate erotic sense. But in the sense of a meeting of two people who need each other and complement each other so well that their connection extends beyond mere friendship. A young boy skipping school becomes intrigued by a woman who is sitting in the park one weekday morning drinking beer and eating chocolate… I get it. Who wouldn’t be intrigued. So begins the connection of these two characters in what is a really incredible character study. The filmmakers manage to jam more characterisation and interesting back-story into these 44 minutes than most filmmakers can manage in a film three times that length (six times that length if your name is Peter Jackson). One is an old fashioned soul who dreams of being a shoemaker. The other is a person who for whatever reason cannot bear to face her workplace. Together they manage to find in the other what they need, at least for a short period of time.

You often hear animators talk of the challenge that is animating water. Those behind The Garden of Words almost thumb their noses at this by opening the film with shots of an incredibly clear lake being broken by rain drops. Much of the film takes place in the pouring rain and it still manages to look sharp as anything. The animators also do incredible work of contrasting the urban and the natural. Shots of a park are cut against close-ups of a racing train wheel. Indeed this park, a natural oasis amongst the grime of the city, is where the two main characters spend most of their time. Technically the film is faultless. As a drama script, the writing is borderline perfect, not being afraid to write something thematically that is really quite adult in its intended audience. For my personal tastes, one scene toward the end did get a little too sentimental. But I am nitpicking and it did not affect my enjoyment of the film in any way. The film is ‘shot’ really creatively too, with montage, close-ups and shot composition all being used to make this a really fun and beautiful film to look at.

It has been a while since I can recall being so enamoured with a film. I just found my self so thoroughly bought in to the narrative on the screen and the two main players bringing it to life. Playing at times almost more like a hymn or a song, The Garden of Words is one to definitely check out.

Verdict: Longneck of Melbourne Bitter

This week thanks to Madman Entertainment, you have the chance to win a copy of Ace Attorney plus two other Japanese films on DVD. Head here for all the details on how to enter.

Like what you read? Then please like Not Now I’m Drinking a Beer and Watching a Movie on facebook here and follow me on twitter @beer_movie.

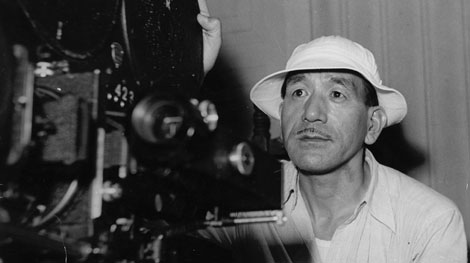

The Cinema of Japan: Tokyo Story

After Chris’s fantastic personal introduction to the works of Yasujiro Ozu yesterday, I thought I would take a look at probably his most famous work – Tokyo Story (1953). I was lucky enough to see the film on the big screen at the Arc Cinema here in Canberra where the film got a really great intro from the head of programming. One of the interesting things he said was that back in the day Ozu was considered “too Japanese” to really succeed internationally. Whilst I love this film and Ozu’s fame obviously extended far beyond his own country, it is pretty easy to see why that opinion was held about him.

Narrative-wise, the film is gentle but not exactly slow. The influence of Ozu on a myriad of artistic filmmakers that would follow him is plain to see in this regard. Tokyo Story’s greatest lesson is just how intriguing an utterly simple tale can be. The script is wonderful, even though it is telling such a simple story. Often it is hard to make these kinds of stories feel authentic, but there are no such issues here. The script allows the plot to unfold languorously in front of the viewer, spiced with an occasional note of humour. There is a sense throughout that Ozu is gently toying with the filmic form in this film. It gently nudges the heartstrings without pummelling them. It also veers in the second half into something of a road movie, where the personal or spiritual journey is accompanied by a physical one. This all builds to an emotional highpoint that I will not reveal except to say that it gives the film a ‘second wind’ of sorts after it had begun to drag for me, ever so slightly.

Narrative-wise, the film is gentle but not exactly slow. The influence of Ozu on a myriad of artistic filmmakers that would follow him is plain to see in this regard. Tokyo Story’s greatest lesson is just how intriguing an utterly simple tale can be. The script is wonderful, even though it is telling such a simple story. Often it is hard to make these kinds of stories feel authentic, but there are no such issues here. The script allows the plot to unfold languorously in front of the viewer, spiced with an occasional note of humour. There is a sense throughout that Ozu is gently toying with the filmic form in this film. It gently nudges the heartstrings without pummelling them. It also veers in the second half into something of a road movie, where the personal or spiritual journey is accompanied by a physical one. This all builds to an emotional highpoint that I will not reveal except to say that it gives the film a ‘second wind’ of sorts after it had begun to drag for me, ever so slightly.

Visual poetry is one of those film terms that gets thrown around far too liberally when in fact I think as there are actually very few proponents of it. That said, Ozu is definitely part of that select group. Here, he continually incorporates architecture and the lines of buildings into his beautiful shot composition. This is notable due to the fact that much of the film takes place in urban areas and Ozu’s adeptness at incorporating enclosed physical spaces into his work makes it a lot prettier to look at then it otherwise would have been. Like the plot and the visuals, the soundtrack to the film can essentially be summarised as being quiet but masterful. Not at all intrusive, the soundtrack makes itself known through an occasional flourish that really enhances what is on screen.

Whilst there is much here that supports the idea that Ozu is a distinctly, if not totally “too Japanese” a director, such as the settings and culture which really could be nowhere but that country, there are also a number of universal elements. Thematically, the concern of parents for their children when they leave home is something that permeates much of the film. Just as this was a major theme of life in 1950s Japan, so it was in 2000s Australia when I left home. If you have left home, you know what I am talking about. If not, then trust me it is coming. More broadly, the film touches on a number of issues related to familial relations, especially the notion of the in-laws and the strains they can place on everyone. The joys that having your family extended by the incorporation of said in-laws is also displayed on screen. Tokyo Story also hit home for me in its exploration of the notion of time. More specifically, the way that we always seem far too busy. Too busy for what is really important. It is a real takeaway from the film and a credit that it is a message that gets through to me, despite leading a totally different life to the ones being led onscreen.

Whilst there is much here that supports the idea that Ozu is a distinctly, if not totally “too Japanese” a director, such as the settings and culture which really could be nowhere but that country, there are also a number of universal elements. Thematically, the concern of parents for their children when they leave home is something that permeates much of the film. Just as this was a major theme of life in 1950s Japan, so it was in 2000s Australia when I left home. If you have left home, you know what I am talking about. If not, then trust me it is coming. More broadly, the film touches on a number of issues related to familial relations, especially the notion of the in-laws and the strains they can place on everyone. The joys that having your family extended by the incorporation of said in-laws is also displayed on screen. Tokyo Story also hit home for me in its exploration of the notion of time. More specifically, the way that we always seem far too busy. Too busy for what is really important. It is a real takeaway from the film and a credit that it is a message that gets through to me, despite leading a totally different life to the ones being led onscreen.

Gentle and artistic, but definitely not boring, Tokyo Story is definitely one to tick off for all major film buffs. It did go on a little too long for me, but Ozu is one of the true original maestros of cinema history. There is a fair chance that he has greatly influenced one of your favourite directors with his approach to the artform.

Verdict: Pint of Kilkenny

Progress: 93/1001

This week thanks to Madman Entertainment, you have the chance to win a copy of Ace Attorney plus two other Japanese films on DVD. Head here for all the details on how to enter.

Like what you read? Then please like Not Now I’m Drinking a Beer and Watching a Movie on facebook here and follow me on twitter @beer_movie.

The Cinema of Japan Guest Post: A Personal Introduction to Yasujirō Ozu

My man Chris Smith, all round legend and contributor to Film Blerg has kindly hooked me up with this brilliant personal intro to one of the true cinematic legends to come out of Japan. Read and enjoy. This is some seriously good shit.

“Sooner or later, everyone who loves movies comes to Ozu”.

So begins Roger Ebert’s Great Movies review on Floating Weeds (1959), the first film I saw of the legendary Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu, and so right he was. I’m not sure what took me so long. I think I’d started watching one of his films before, maybe it was this one or perhaps it was Tokyo Story (1953), the other Ozu film that seems to have infiltrated the zeitgeist outside of Ozu’s work itself. Whichever it was, I remember watching the first few minutes and finding it challenging; first visually with the compositions, and then the slow, deliberate pacing; but man am I glad I stuck with it, because in the films of Ozu we find what might be the purest and most beautiful expression of people and their humanity in perhaps the entirety of cinema as an art form.

As a visual film maker, Ozu is a stylist to the point of anti-style. His films are deliberately (and misleadingly) simplistic with scenes often playing out in extended shots (generally low angles), very little camera movement (by the later stage of his colour films the camera ceases to move at all), and often breaking the rule of the “hypothetical camera” (the disorienting effect where the viewer becomes aware that the camera or lens from which they’re seeing this world, which we know must be somewhere, has its space physically taken up by something else – in Ozu it is the reverse angle of two characters talking across from one another).

Narratively, Ozu’s films are mostly anti-climactic with seemingly important events of narrative action usually happening off-screen and what was previously thought to be of so much importance is referenced in simply passing, as so often happens in real life once important events are swallowed up by the past.

So if his films are visually mundane (they’re not) and his plots are uninteresting (again, they‘re not), why is Ozu treated as cinematic royalty? It’s because with the relative removal of these exterior concerns, Ozu focuses on the heart of his stories, which are his characters and their emotions, which we remember long after visual and narrative details have faded in our memories.

The effect of watching a good many of Ozu’s films in quick succession (especially his later work which has been boxed together by Criterion in their Eclipse series) is very much like binge watching your favourite TV show, even a soap opera – just without all the heightened melodrama – as his stable of fine actors, including Ganjiro Nakamura, Shin Saburi and Chisu Ryu – navigate the terrain of Ozu’s thematic concerns (tradition vs. modernity, women’s independence, family relationships) often in the same locales and sets (the majority of these stories tend to play out in traditional Japanese apartments). Like with television, the audience’s investment lies less with the week to week plot, but more with how the characters we love deal with conflict, and it’s these conflicts that lead to the greatest moments in Ozu.

From the old widow O-tane (Choko Iida) of Record of a Tenement Gentlemen (1947); who after neglecting the young lost boy who attaches himself to her and treating him horribly, finally comes to find that she in fact does love him as a mother – only for the boy’s father to come for him just after she’s made this discovery; to the heartbreaking scene of Flavour of Green Tea Over Rice (1952) when Mokichi (Saburi) tells his wife (of an arranged marriage) Taeko (Michiyo Kogure) after they’re been married for many, many years that they simply aren’t happy, the world of Ozu is populated by real people we become deeply invested in, often in what may seem like small irrelevant details, but they become so important in the context of his cinematic world.

While a good deal of has been written about the final scene of Late Spring (1949) (the films plot involves an ageing and widowed professor (Ryu) being convinced to arrange for his daughter (Setsuko Hara) to be married to a stranger so she’ll be taken care of once he dies, but she refuses because she wants to stay with her father, leading him to pretend to marry as well) where the daughter says goodbye to her father and the father returns home alone; my own personal favourite moment in Ozu is in his reworking of Late Spring, Late Autumn (1960). Hara, now the parent, confesses to her daughter Ayako (Yoko Tsukasa) that she has decided not to marry but to live alone while her daughter leads her own life. It’s one of the most poignant and touchingly simple moments in the history of film that always invariably leads to tears from its audience.

I’ve touched on only a few of Ozu’s individual films here and barely scratched the surface of what makes him such an incredible filmmaker, but his entire filmography is a rich and rewarding journey that awaits all film lovers, that as Ebert says, find their way to it.

Chris Smith is a Melbourne based freelance writer who is passionate about film, books and music. His work is often featured on Film Blerg and various other places.

This week thanks to Madman Entertainment, you have the chance to win a copy of Ace Attorney plus two other Japanese films on DVD. Head here for all the details on how to enter.